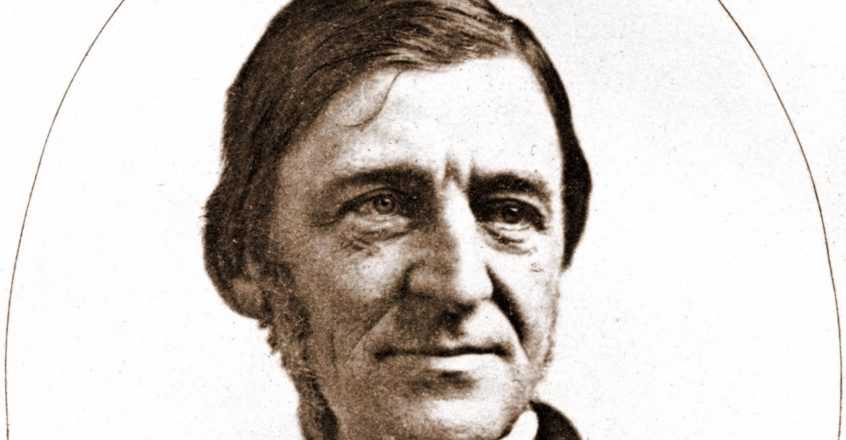

Ralph Waldo Emerson and The Origins of the Spiritual But Not Religious

March 15, 2017

It is not uncommon today for people to describe themselves as spiritual but not religious. This trend is a direct result of the secularization process that began during the Western Enlightenment. During the span of about 200 years science and reason began to increasingly dominate the modern mind leaving religion and spirituality on the defensive throughout the Western World. Some defenders of faith argued that this trend marked the end of civilization. Others attempted to use reason to generate powerful metaphysical arguments to prove the existence of that which could not be seen. Still others searched for and developed “alternative” spiritual views that they hoped would reconcile science and spirit.

Ralph Waldo Emerson and William James are two prominent American thinkers who attempted to carve out a place for spirituality somewhere in the grey zone between scientific materialism and religious orthodoxy. The ideas of these two thinkers led to the creation of an alternative spiritual tradition in America. They inspired New Thought Churches throughout America and created the foundation for the spiritual movements of the 1950’s and 60’s, and the “East meets West” spiritual paths that have become so popular.

This stream of alternative spiritual thought can most directly be traced back to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s famous “Divinity School Address.” In the summer of 1838 Ralph Waldo Emerson was invited to speak to the graduating class of the Harvard Divinity School where he himself had been trained as a minister years before. On that day he gave a blistering speech creating an uproar among the spiritual and religious elite of New England that didn’t die down for over a year.

Tensions between the established orthodoxy of the Calvinist church, more liberal Unitarians, and brazen young Transcendentalists like Emerson had been building up for some time. Emerson’s unabashed critique of the church during his divinity school address to a group of newly trained ministers was more than enough to catalyze a spiritual explosion.

That day Emerson addressed a small audience of students, friends and Harvard officials, and delivered a searing indictment of a Christianity that he accused of robbing human beings of their natural divinity. Emerson saw Jesus not as especially blessed but as the greatest example (so far) of what all human’s could and should aspire to. In his own worlds:

“Jesus Christ belonged to the true race of prophets. He saw with open eye the mystery of the soul. Drawn by its severe harmony, ravished with its beauty, he lived in it, and had his being there. Alone in all history, he estimated the greatness of man. One man was true to what is in you and me. He saw that God incarnates himself in man, and evermore goes forth anew to take possession of his world.”

Emerson accused the church of two errors. The first was that the church had elevated the figure of Jesus Christ to a station above the rest of humanity creating a cult of personality around him.

“Historical Christianity has fallen into the error that corrupts all attempts to communicate religion. As it appears to us, and as it has appeared for ages, it is not the doctrine of the soul, but an exaggeration of the personal, the positive, the ritual. It has dwelt, it dwells, with noxious exaggeration about the person of Jesus.”

In doing this the church had relegated the holy to something that had happened in the past and did not recognize that true spiritual emancipation was available for all of us here and now.

“Men have come to speak of the revelation as somewhat long ago given and done, as if God were dead. The injury to faith throttles the preacher; and the goodliest of institutions becomes an uncertain and inarticulate voice.”

The second error of the church leads directly from the first – its preachers are largely uninspired by authentic spiritual experience and teach the gospel largely from an intellectual understanding rather than living revelation. Because of this they are unable to provoke a genuine experience of the divine in others.

“The spirit only can teach. Not any profane man, not any sensual, not any liar, not any slave can teach, but only he can give, who has; he only can create, who is. The man on whom the soul descends, through whom the soul speaks, alone can teach. Courage, piety, love, wisdom, can teach; and every man can open his door to these angels, and they shall bring him the gift of tongues. But the man who aims to speak as books enable, as synods use, as the fashion guides, and as interest commands, babbles. Let him hush.”

Emerson felt it was his duty to liberate a new generation of ministers to strike out on their own, and find immediate access to Truth as it is found in one’s own soul and not in scripture.

“Yourself a newborn bard of the Holy Ghost, — cast behind you all conformity, and acquaint men at first hand with Deity. Look to it first and only, that fashion, custom, authority, pleasure, and money, are nothing to you, — are not bandages over your eyes, that you cannot see, — but live with the privilege of the immeasurable mind.”

Perhaps Emerson should have anticipated how enormously inflammatory his address would be. Yet he never quite seemed to understand how he could have caused such a tremendous public backlash. Over the course of the next few year’s Emerson was propelled into spiritual superstardom and a true path for spirituality outside of any religious tradition was born.